In the fast-moving world of small and mid-size business (SMB) competition, sustainable differentiation is often the difference between a company that thrives long term and one that fades into irrelevance. While enterprises typically have the capital to weather competitive pressures or acquire innovation, SMBs must rely on sharper positioning, deeper customer insight, and the creation of meaningful competitive moats. A moat is any defensible advantage that discourages competitors from attacking the same customers with interchangeable products or services.

Understanding the Modern Moat

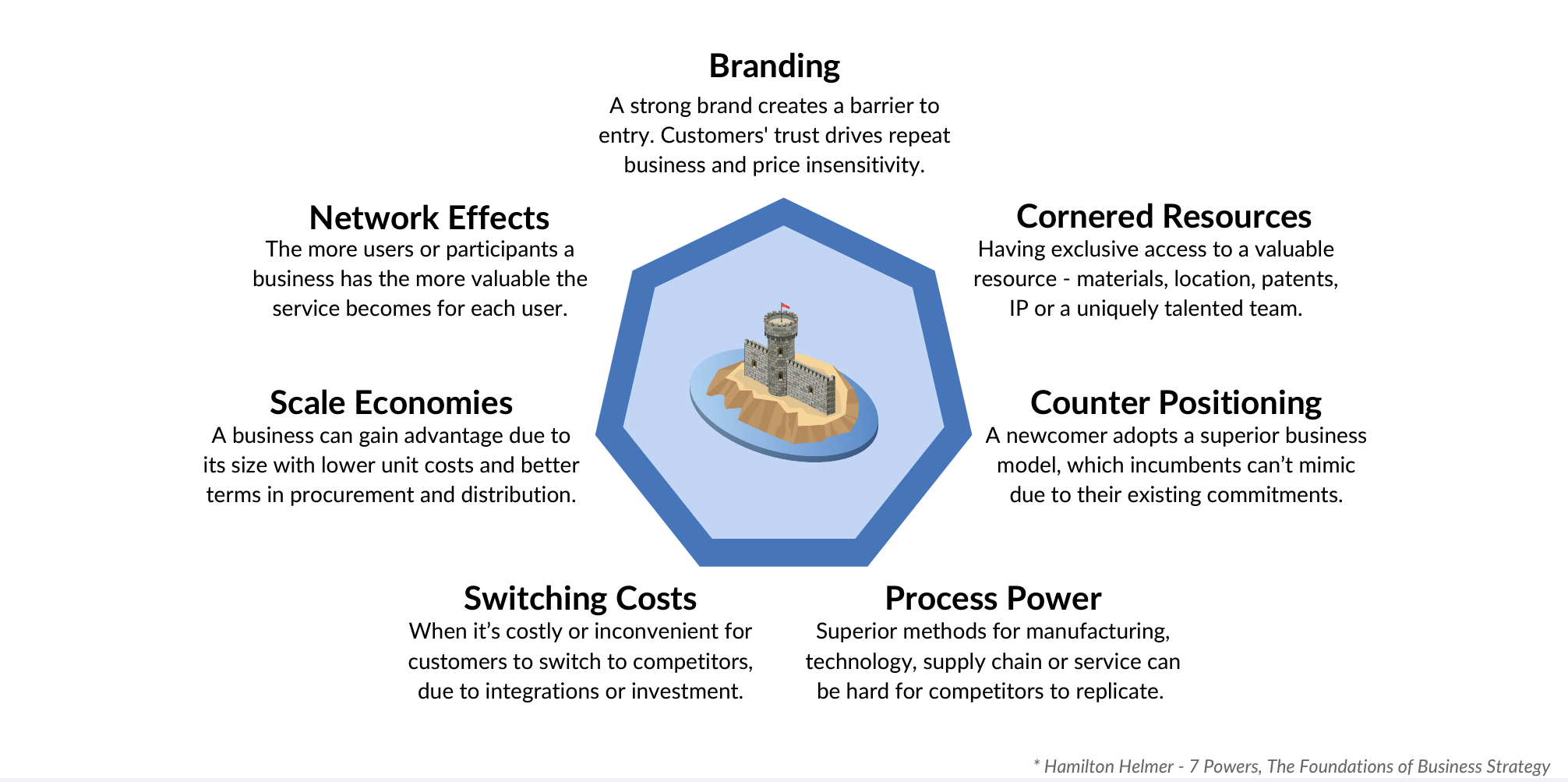

Traditional moats focused heavily on scale, capital, and cost. The digital era has reshaped that definition, elevating moats based on data, platform integration, brand affinity, customer experience, and intellectual property—each of which can compound over time.

For SMB founders, recognizing that they can create moats is crucial. Moats are not reserved for Fortune 500 firms. In fact, because SMBs tend to innovate faster and closer to customers, they can form niche moats with startling durability.

Common Types of Moats for SMBs

Below are several categories that often apply directly to small and mid-size operators:

- Brand and Trust

When customer experience consistently exceeds expectations, trust compounds. Trust is notoriously hard to replicate and acts as both a price-insulation mechanism and referral generator. - Customer Switching Costs

Tools, platforms, or services that integrate deeply into a client’s workflow create friction for switching. Subscription SaaS companies are renowned for leveraging this dynamic. - Exclusive Data or Knowledge

SMBs in specialized markets can own proprietary processes, know-how, or datasets developed through years of engagement. - Specialized Operational Capabilities

Speed, customization, craftsmanship, and flexible capacity often give SMBs operational moats larger firms struggle to emulate. - Partnership and Ecosystem Integration

Businesses that plug into valuable ecosystems—vendors, associations, or co-marketing arrangements—can build mutually reinforcing supply-side and demand-side advantages. - Infrastructure and Physical Barriers

Local dominance, geographic positioning, or specialized equipment can make competition unprofitable.

Diagnosing Which Moats Already Exist

Most SMBs already hold fragments of a moat without realizing it. The challenge is converting fragments into a system. A diagnostic framework can help:

- What unmet need do we serve that competitors overlook?

- What takes us years to build that others cannot copy quickly?

- What frustrates customers about industry alternatives that we excel at?

- What friction would a customer face if they switched away from us?

- What pieces of our process or knowledge are proprietary or tacit?

- Where do we consistently win business and why?

Founders who ask these questions often uncover strong moats buried beneath day-to-day operations.

Strategic Positioning and the Role of the Market

Sometimes moats are contextual. A small HVAC installer in a rural region may possess a geographic moat simply because competitors are not incentivized to enter the same market. Niche manufacturing firms often enjoy scale moats because demand volumes are too small for larger firms to find attractive.

In other situations, the moat is relational—built through social capital, generational continuity, or institutional knowledge passed through teams. As private equity firms increasingly target SMB acquisitions, relational moats are becoming more visible and valuable.

One Keyword Paragraph (single usage)

When evaluating a company’s defensibility, investors and advisors sometimes deploy structured business moat analysis frameworks to examine the durability, imitability, and compounding strength of its competitive edge without relying solely on financial statements or short-term performance.

How SMBs Can Strengthen and Extend Their Moats

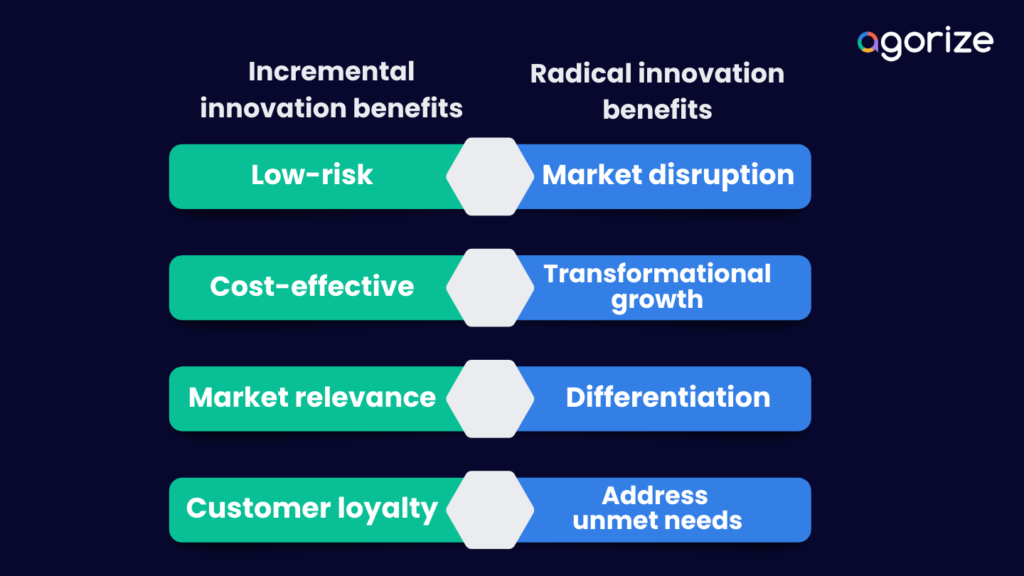

Once a moat has been identified, the work shifts toward extension. Moats can erode quickly if left static. The strongest moats are dynamic enough to support innovation, yet stable enough to remain recognizable.

Ways to extend an existing moat include:

- Formalizing processes into proprietary methods or certifications

- Capturing customer knowledge into CRM or data-driven workflows

- Strengthening after-sales experience to reinforce trust loops

- Verticalizing offerings to lock-in ecosystem synergy

- Turning bespoke knowledge into defensible intellectual property

- Applying automation to scale what makes the business unique

- Increasing switching costs through subscription, integration, or bundling strategies

The goal is to convert temporary advantages into enduring ones—without compromising agility.

The Exit and Valuation Impact

For entrepreneurs considering future exits, moats materially affect valuation, buyer demand, and negotiation power. Acquirers pay premiums for defensibility because it reduces risk. The rise of SMB rollups, search funds, and micro-private equity has made moat articulation more important than ever. A strong moat not only commands higher multiples, but can widen the buyer pool dramatically.

Case Study Reflections From the Market

Recent business coverage indicates that private investors increasingly value “durability over disruption,” especially in sectors such as industrial services, B2B manufacturing, and regional logistics. These industries favor operators with entrenched relationships, certifications, regional infrastructure, or specialized capabilities—precisely the types of moats SMBs specialize in building quietly over decades.

In parallel, digital-first SMBs in e-commerce, education, and SaaS are proving that niche digital moats—communities, platforms, data, and integrations—can hold formidable value even with small teams.